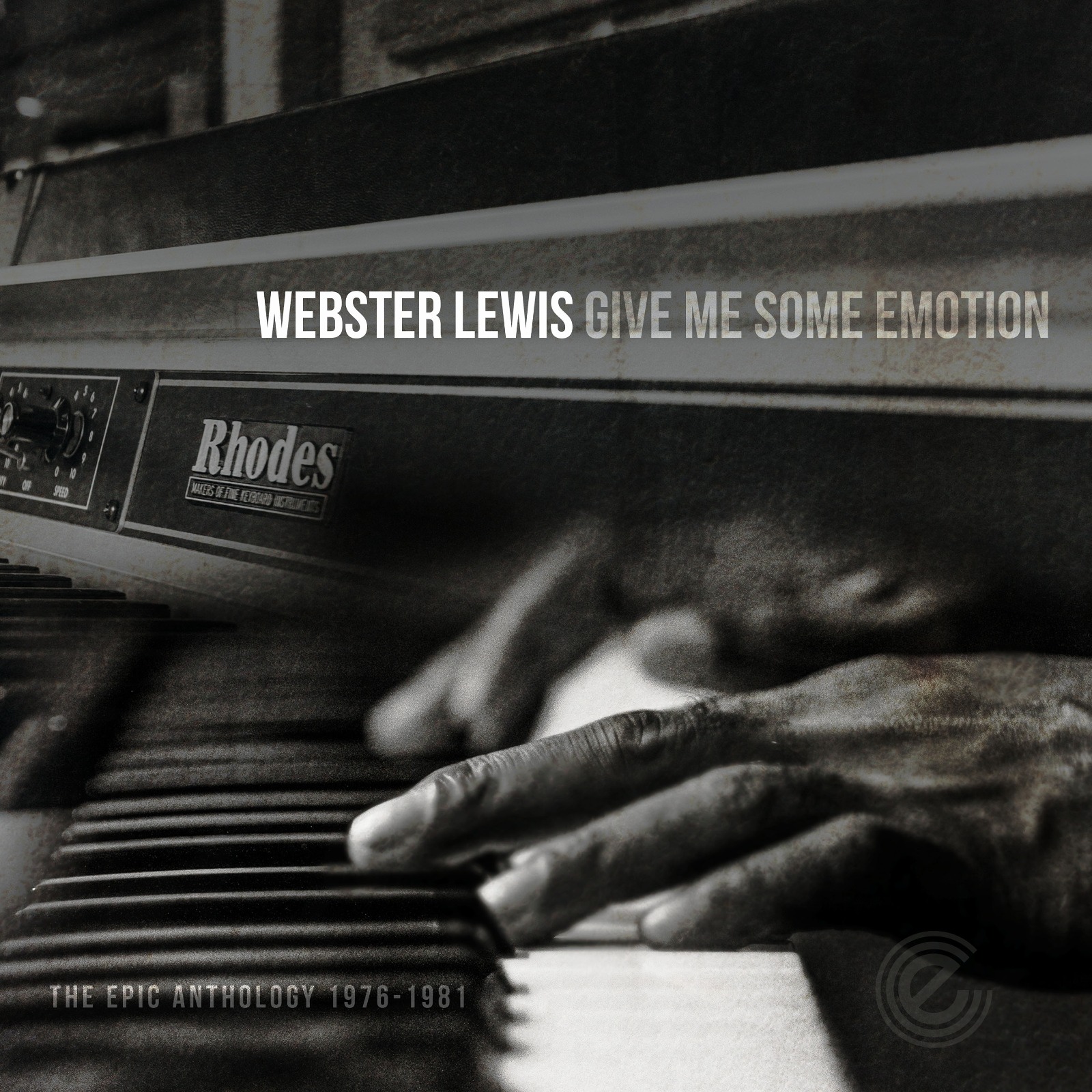

![]()

Webster Samuel Lewis Jr was born 1st September 1943 to Webster S. Lewis Sr. and Virgie Gaines Lewis in Baltimore, Maryland. From a young age, Lewis’ talent was self-evident and, with the encouragement of his family, he would be put on an inexorable path to a long and fruitful musical career. Lewis lived a full life of music, although he didn’t see the commercial success that he arguably deserved during his tenure as a bandleader: he was not a front man of his day and much of music became better known retrospectively. Aside from his sideman duties with the likes of Kimiko Kasai, Merry Clayton and Michael Wycoff, his solo material was not widely known until the first wave of the rare groove scene in the early eighties, where British DJs rediscovered his unjustly neglected works. He was, however, a significant figure in the niche and loosely defined world of jazz-funk, who delivered several high-quality albums that are increasingly collectible and expensive titles in today’s marketplace.

Lewis was educated at Morgan State University, a historically black college in Baltimore where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Sociology. He would transition from the humanities to the arts, completing a Master’s degree at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston studying under American Jazz trumpeter Gunther Schuller, even becoming associate dean from 1972-1978. Lewis’ initial forays led him to work with Tony Williams, George Russell, Bill Evans and Stanton Davis, while honing his craft on keys throughout the 1960’s. In the early 1970’s, Lewis embarked upon a tour of Scandinavia, setting up shop in Norway where he released two albums and wrote material for local musicians—namely Arne Falck and Brett Borgen’s 72’ album Menneskedøgn—under the pseudonym Webster Lewis and the Post-Pop Space-Rock Be-Bop Gospel Tabernacle Orchestra and Chorus BABY!

The first release and his finest work from this period was called Live at Club 7, recorded at the eponymous arts venue in Oslo. The 20-minute-long opening salvo Do You Believe accrued a delayed and cultish popularity in the UK, becoming a rare jazz-dance classic a few decades later: it took pride of place on Russ Dewberry and Jake Behnan’s 1997 compilation Freedom Time on Counterpoint, comprised of popular tracks played at the Brighton Jazz Rooms. The musical content of Live at Club 7 runs the gauntlet between fusion, post-bop, gospel and soul, an album that has since been reissued in 2007 on Jazzaggression and P-Vine Records. It showcases a rawer and edgier side of Lewis’ musical output, in stark opposition to the smoother aural textures of his Epic material. Lewis plays organ on these recordings, muddy sounding and ferocious, the players around him smoking in between sweltering, deep-pocketed grooves and moods, with Lewis stoking the furnace.

Not much is heard from Lewis over the next 4 years, although he does have some recorded music on Strata East, appearing on two albums from The Piano Choir: Handscapes (1973) and Handscapes 2 (1975) featuring the very first recording of Barbara Ann, spiritual jazz outings comprised of jazz pianists ranging from Stanley Cowell, Harold Mabern and Sonelius Smith. He signed a record contract with Epic in 1976, recording his debut US release On the Town the same year. There is more of a commercial angle to this musical output where Lewis presents a sound categorically different from his earlier jazz, building on trends such as soul, disco and jazz-funk. The music is well polished, luxuriously produced and replete with string sections and the disco sheen of orchestral backing. The album also boasts a personalised sleeve note from Roberta Flack, who says of Lewis “Webster Lewis is a friend. My feelings about the quality of his musicianship can be summed up in one word, genius… Webster is committed, and it shows”. Clearly, he had spent his time nurturing a reputation as one of the hot young arrangers and instrumentalists of the day—plaudits from the likes of Roberta Flack don’t come cheaply. On this album, Lewis cements his credentials with Love Is the Way, a track that exudes elegance with sophisticated, glossy production and delicate interplay between keyboards and vocals, a select 12” from the album. The standout track—a UK only seven—and bona fide album highlight Do It With Style dazzles with an accelerating dynamic shift, sunshine harmonies, soulful orchestration and accomplished arrangements, exemplary of Lewis’ burgeoning potential as a composer and musical arranger: a litmus for things to come.

Following this release came one of his finest outings, Touch My Love, released in 1978, a year that would also see Lewis session on Paul Jackson’s fusion classic Black Octopus. Musically, it is jazzier than his previous album, putting him in similar stead to contemporaries Herbie Hancock, Mtume and Donald Byrd, all of whom had migrated from straight-ahead jazz to fusion and jazz-funk by the mid-seventies. Touch My Love still retains orchestral elements, tooled up with large string and horn sections—the production budget on this album must’ve been enormous—while delving into mesmeric fusion and pulsating jazz-funk grooves. The set smacks of class, a joyous outing of late seventies fusion verging at times on smooth but with just enough danceability and tempo to transcend that tag. Set highlights include the opening track Hideaway, a quickfire number scored with lush strings, cascading acoustic piano and beautiful harmony vocals, and There’s A Happy Feeling, a track that starts cooking from the mid-way breakdown, out of which an extended refrain of the chorus—coloured with deep, throaty clavinets, funky basslines, rumbling congas and hard breathing horns that hit the sharpest and most incisive of chromatic changes—takes things in its stride. The unreleased Japanese Umbrella features from the same session, a lengthy and lesser-produced jazz-funk demo take where the rawness of Lewis’ electric piano is accentuated, a track that sounds as though it could have been lifted from the Uno-Melodic catalogue, putting him in the same bracket as Tarika Blue and Justo Almario. The lack of overt production here also gives you an intimate and undiluted portrayal of Lewis’ abilities as a keysman.

The album’s magnum opus, and one of Webster’s best, is the Latin drenched fusion of Barbara Ann, a gorgeous groove and a huge crossover dancefloor jazz play for Soul Mafia DJ’s Tom Holland and Pete Tong when it was released—although copies were extremely limited to the buying public. A gentle montuno performed on Fender Rhodes sits above a shuffling, samba infused drum pattern, underlaid with rigid bass work and accented with sensuous melodic phrasing and buttery vocals. These are provided by Barbara Ingram—one part of the Jazz-Funk group Ingram and possibly a source of titular inspiration. It is a monumental record in Lewis’ cannon and a seminally important London dancefloor jazz play, notably re-popularised by Louie Vega’s Elements of Life. By the end of the 1980’s, London based DJs Gilles Peterson and Patrick Forge would give Barbara Ann a new lease of life at the legendary Sunday Afternoon at Dingwalls in Camden, where the track became an underground jazz-dance classic. Patrick Forge remarks upon the cultural significance of Barbara Ann and the impact of the track on the UK club scene at the turn of the acid house era, a song that’s overwhelming happiness chimed with audiences during the second wave of the summer of love in 1990:

“Perhaps Barbara Ann wasn’t designed for the dancefloor, there couldn’t have been many discos playing samba fusion cuts in the late seventies, but maybe in the UK where the seeds of jazz-dance culture were being sown, Barbara Ann got some love. Certainly as that culture burgeoned through the eighties it started to become a staple of discerning DJs. By the time I came in towards the end of the decade, Barbara Ann was set to become an anthem, the lyrics, “Can’t you see? You and me, ecstasy” took on an extra meaning as the second summer of love resonated in clubs beyond the big raves. And so it was on Sunday Afternoon’s At Dingwalls where Barbara Ann was dropped more often than not in Gilles Peterson’s sets to an always euphoric reaction. Barbara Ann’s combination of unbridled sensuality and driving polyrhythmic intensity has an irresistible energy, a visceral charge and an ethereal fizz.

Recorded in those halcyon days when both analogue studios and session players were at their peak, isn’t it about time the high art and craft of this music was properly celebrated? Although neither commercially mainstream or highbrow, Webster Lewis made music that is both vastly accessible and eminently sophisticated, his oeuvre comfortably straddling jazz and soul. Yet so much of this music with its disco era gloss is derided as being too lightweight for jazz heads and too smooth for those in search of authentic soul. However, the level of innovation and musicality shouldn’t be dismissed, there’s nothing ersatz, musicians like Lewis were bringing a thoroughbred musical and production nous to their work.

The groove of Barbara Ann is derived from samba but has shifted away from its native swing. The rhythm is more “pushed” with drums that have something of a funky shuffle and implied backbeat, an exercise in high calibre rhythm section with drums and bass thoroughly locked around Webster’s highly percussive Fender Rhodes. Such Latin hybridisation was rife in this era, echoing the pioneering work of bandleaders like Ricardo Marrero whose group featuring both Dave Valentin and Angela Bofill carved out a unique brand of NYC Latin fusion with their albums in the preceding years. The melding of rhythmic sensibilities from both Afro-Cuban and Brazilian sources was a trick that many tried, but few with as much success as Webster Lewis, his other jazz-dance staple, El Bobo being a classic example. Though Barbara Ann leans emphatically towards Brazil, a disco era samba that still frees hips, induces smiles and raises hands in the dancefloor, pure uplift.”

Following from Touch My Love, Lewis found employment with jazz giant Herbie Hancock, accompanying him as musical director for the international tour of vocoder-led albums Sunlight and Feets Don’t Fail Me Now in 1979, playing electric piano, synthesisers and organ. Footage exists from this period, depicting Hancock as a keytar-wielding, vocoder-breathing front man decked out in open shirted, statement collared regalia, with Lewis as a smooth background fixture amid an impressive poly-rig of keyboards, even harmonising with Hancock on a second vocoder. Lewis’ selection in Hancock’s band evidences his well-regarded skills as a pianist and go to synth merchant, Hancock especially known for choosing high-quality sidemen to tread the boards with him, his vested faith in Lewis clear testament to his abilities—perhaps even his value for money. The only recorded albums featuring Lewis and Hancock together are the live Japanese album Directstep, Kimiko Kasai’s Butterfly and the third Epic album in Lewis’ cannon, 8 For the 80’s.

Hancock was a key fixture on the 1979 album 8 For the 80’s, an album that he would co-produce and arrange. His appearance is marked on the quiet storm crossover track The Love You Give To Me, a soaring confluence of jazz-fusion and soul, which some commentators have made a case for as ground zero for smooth jazz. Featuring a wide palette of synth-based sounds and sultry vocals, underpinned with the subtle squelch of Hancock’s vintage clavinet sound riding the rhythmical wave in the background, accenting passages with his masterful playing. Lewis also finds space to express himself with a low-key Rhodes solo which pieces together and abstracts the changes in delicate, light-footed style. In commercial terms, Lewis reached his greatest heights with the two-step cut Give Me Some Emotion co-written alongside Hancock, possessing a similar sound to some of Herbie’s later CBS output on Magic Windows, tonally close to the likes of Satisfied With Love and Tonight’s The Night. The track was almost immediately covered as a successful solo single for Merry Clayton, the title track behind her 1980 album Emotion on MCA, the only track that Lewis would appear on and arguably a better-known interpolation than the original.

His fourth and final release on Epic was the 1981 album Let Me Be The One, for many his finest and most collectable work. The pedigree of the featured musicians on this set raises the bar, from Skip Scarborough, Willie Bobo, Paulinho da Costa, George Bohanon, Oscar Brashear and Jim Gilstrap. Scarborough would also contribute co-songwriting and production credits on several songs, as well as Columbia Records’ A&R and Marketing Vice President Raina Taylor, Violinist Charles Veal Jr. and legendary saxophonist Bernard Ighner. The album is telling of the period where big budget soul was fused with jazz-funk, recorded and produced with a recording budget and large-scale personnel which present day artists could only dream of. Album highlights include the instrumental classic El Bobo, named after the guest percussionist, a fine combination of up-tempo jazz-funk and Latin styles of playing, an underground fusion anthem that would appear on countless compilations as well as receiving regular play from the likes of Robbie Vincent and Norman Jay. Dancer is a coruscating, ascendent number, backed up with the full weight of a prominent horn section, nuanced with understated percussive influences, background synths and iced out electric piano manoeuvres that take it to the stratosphere. Let Me Be The One is a shuffling up-tempo number in which slap bass takes a prominent role in marshalling together the rhythm section, while You Are My Life reaches similar musical territories, a vintage Webster Lewis composition where Mary Dean Moss’ deep vocal is an instrumental facet, alongside clever orchestral voicings, muted trumpets and subtle inflections of flute. The unreleased tracks from this session Boston and Reach Out feature an uncredited female vocalist who hits vocal territories akin to Phyllis Hyman, soulful and ebullient numbers that make you question why they were left off the original album. The album’s title track and Richard Searling modern soul play Let Me Be The One features uncredited vocalist Johnny Baker, his role in the song uncovered some decades after the release.

After Let Me Be The One, Lewis would have one final outing with The Love Unlimited Orchestra on Barry White’s Unlimited Gold label with the album Welcome Aboard, while also running his production company Webo Music, producing artists from Michael Wycoff (Looking Up To You) and Gwen McCrae (Keep The Fire Burning). He also conducted and arranged for many musicians, including Michael Jackson, Tom Jones, Lola Falana and Thelma Houston. Disillusioned with the direction of the music industry and his relative lack of success, Lewis eventually fell out of favour with writing self-produced music for commercial purposes, subsequently moving away from the business to refocus his energies on writing music for TV, advertising and film. Lewis would continue to work in this field before moving back into education in the 1990’s, where he taught jazz voice and arrangement classes at Howard University in Washington as a visiting professor from 1995-1999. Sadly, Lewis passed away at his home in Barryville, New York on the 20th of November 2002 as a result of diabetic complications, leaving behind a wealth of music that has since been rediscovered, recontextualised and reinvigorated by younger generations. As contemporary audiences dig deeper into jazz-funk and fusion than ever before, we present to you a comprehensive collection of Webster Lewis’ most memorable Epic years works, compiled by myself and Ralph Tee with love and admiration.

Emblematic of the period where major labels had money to throw at productions helmed by session men, analogue studios were a sign of the times and high-quality musicians were in unfettered supply: such is Webster Lewis’ music. Luscious, well-produced and melodically sophisticated are adjectives that come to mind when describing his sound, stone-cold and funky tracks adorned with the tonal refinement of jazz and the undulating groove and emotive tug of soul. Compositionally, he would nod to his jazz background while harnessing the contemporary influences of the day, namely soul and funk, while flirting with the possibilities of fusion, Latin and Brazilian music. As a composer and musician, he was deeply underrated, recognised by those in the know—such as Herbie Hancock—but not to the wider listening public. He never truly found the contemporary audiences that perhaps he dreamed of, or even aspired to maintain, his legend built in retrospect rather than contemporaneously, so much so that there is a serious dearth of information about Lewis from this period. There is, however, an equal possibility that he was a man who preferred to live a life behind the scenes as a producer and arranger, someone who gave his most popular track away to Merry Clayton rather than capitalise on it himself, a discreet yet talismanic professional who preferred to get his work done quietly, supported by serious academic credentials. What is certain is the high standard of Webster Lewis’ output, his genius proliferating among cooler heads and savvy collectors, while the prices of his original albums slowly climb. May his music live on for generations to come.

Will Fox – September 2022

Thanks to Patrick Forge, Laurence Prangell, Terry Hall, Gary Dennis and Brook Plumptre for your patience, time and wisdom.